Silke Hesse was among more than 12,000 people who, at the peak of Second World War, were held in internment camps across Australia.

She was almost six years old when she first stepped foot in Tatura internment camp.

Listen as she shares her story experiences of internment.

Music

If I Were You, Alsever Lake

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: The Shrine of Remembrance acknowledges the Bunurong people of the Kulin nation as the traditional custodians of the land on which this podcast was recorded. We pay our respects to elders past and present.

Welcome to the second episode in the Toys, Tales and Tenacity podcast series. In this series, we delve into three stories of how war and conflict have impacted the childhood of three quite extraordinary individuals.

At the peak of the Second World War, more than 12,000 people were held in internment camps across Australia.

Our guest today, Silke Hesse was one of them. When she was six years old, Silke was interned at Tatura. She joins us today to tell her story and share her experiences of interment.

LAURA THOMAS: Good morning Silke.

SILKE HESSE: Good morning, Laura.

LAURA THOMAS: Now I think it's important that you start by sharing a bit of your family history and your background because that plays a really big part in your story. Can you tell me a little bit about your parents and your grandparents?

SILKE HESSE: Yes, my grandfather was a wool buyer from Bremen in Germany. And he came out to Australia in about '96, I think, 1896. And then married and had three children, lived in Hunters Hill, and my father grew up in Hunters Hill. And at the age of nine, I think went to Tudor House, which was quite a well known Junior School for Boys and loved Australia. Then by that time, of course, when he was around 10 or so the world wasn't quite as calm anymore as it had been. And his father had to travel between Germany and, and Australia with the wools each year. And so it didn't really matter very much where the family was. So they decided to move the family back to Germany in time for my father's secondary education. And so he had that in Germany. First in Weisbaden, then in Berlin. And he had a very nice youth, although he always yearned for Australia. And when he could have a holiday in the Bavarian mountains, which reminded him of the free life of Australia, he was always overjoyed. Yes. And then, of course, he was of military age. And the problem was that he was of German parentage, but born in Australia, and by Australian law, he was Australian, by German law, he was German. And when the war began, of course, he was in Germany and considered German. So he was called up when he was 18. And then he had two years of frontline World War One fighting with his first battle being Passchendaele opposite Australians. And in a lull from the absolutely shocking battle, and weather, they were asked to, to go out and and look for people on the battlefield. And he and some others found an Australian, Captain Richardson, who turned out to have been almost his neighbour in Sydney. He, he took letters from from him, to give back to the family. He, he always had this feeling that he was both Australian and German and that he was fighting his school friends probably and others. Yes, anyway, he managed among very few to survive these battles. And sometimes, you know, they were in a trench and, and all the others were killed and he survived. Yes, then he had university training in economics in Germany

LAURA THOMAS: Your father did eventually make it back to Australia where you were born. When did he arrive back here?

SILKE HESSE: In about 29, I think, somewhere around there. And his father wanted him to take over the wool firm, but not just yet. And so he'd be summoned to work there, but there wouldn't really be any good work for him. So he'd be allowed to go off on some adventure again. And among these adventures was one going to New Guinea, where he then ended up on an expedition in search of gold, and with two other German men over there, and that expedition ended tragically one of the men died of amoebic dysentery. And my father also got it and ended up having a very dangerous operation, and survived and then was told to go back to Germany, or go back to a cooler climate for a while. And so he went back to Germany and arrived there just at the time when Hitler was starting to become active. He'd written a book about his experiences in New Guinea. But the depression was so bad that nobody published books. And, yes, anyway, he ended up having to leave Germany because he'd become active against Hitler. And he went to America there, Hollywood, and sort of tried various ways of earning money there. My mother came over and married him

LAURA THOMAS: Your mother, was she Australian or German?

SILKE HESSE: No, she was German. And then eventually, they went back to Australia, and where he then took over the wool business just before my sort of with the retirement of my grandfather.

LAURA THOMAS: So it was quite a journey for your parents, but I'm interested to know what your childhood was like in Sydney.

SILKE HESSE: Yes, my childhood was very, very happy, I think. We lived right on the beach at Collaroy, and when I was two, we went over to Germany and to meet my grandparents and the family and managed to get out just when when it looked as though war was imminent. It wasn't then, but it was soon afterwards. Yes. So we had a, we had a lovely youth right down by the sea, on the beach, and in the lovely garden and all the rest.

LAURA THOMAS: Like an Australian postcard in a lot of ways, isn't it?

SILKE HESSE: Exactly.

LAURA THOMAS: You mentioned it was very happy, but in 1939, when the Second World War broke out, did this change? Did you start facing discrimination because of your German heritage?

SILKE HESSE: Yes, we did. When we children, I was the oldest and my brother, who was a year younger went to kindergarten, the other parents all withdrew their children in protest at having a German child with them. And the kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Burkard said she didn't wage war against children and kept us there. And after a fortnight, the others came back. And I remember we were asked, I don't know whether that went on, but to work at another, at a separate table, which didn't really sort of matter much to us. But this sort of patriotic reaction of people. Yes, Australians fell into two categories. Some were absolutely amazingly lovely and generous. And the others sort of felt that they had to do something for Australia's national honour or whatever it was. And, yes, so we had both and since an aunt of mine who was with us, kept a diary of of what we said and so and I also have a feeling that I know you know what I actually what went on and what what I thought about things at the time. Yes.

LAURA THOMAS: And because you were quite young at this stage, did you have a concept of, of why you were being treated differently? Or kind of what was going on? Or did it just kind of seem like...

SILKE HESSE: No, I did have a concept and I think there must have been, must have talked about it among other things, like, sort of in my games, I called myself Mrs. Peace. And yes, and we spoke both languages, but we had to finish the sentence in English when we crossed the threshold.

LAURA THOMAS: Right. As in when you were leaving home.

SILKE HESSE: Yes. So we, we had very strict borders between the two. And we had, we had been sort of, the long reef then became a sort of military training ground. And my brother and I each managed to get a soldier for ourselves, and, and play and whenever these were sort of off duty, they came and played with us.

LAURA THOMAS: When you say they were at Long Reef, that was just behind your house, wasn't it? So you were seeing this on a regular basis?

SILKE HESSE: Yes, bordering on the Long Reef golf course. And that was lovely until my brother's soldier, Jim. Mine was Mac, the gun went off. And, and after that, we couldn't play with soldiers anymore. But that was quite good, because from then on, I think soldiers in khaki had a good image for me. And we then yes, my father was then interned. I remember the day when he was interned, and there were these people that sort of, yes, I didn't know in the house, and then he went off with them and disappeared.

LAURA THOMAS: In hindsight, and from research, you've been able to find out exactly why your father was interned. But at the time, you didn't know. Can you explain now what the steps were in in him becoming interned and how that came to be?

SILKE HESSE: He was asked whether he wanted to shed one of his nationalities. And I think if he had he'd probably would have been sent to New Guinea where he had experience. But he said that he didn't want to give up either of his nationalities. And the result was that they decided that he'd had had to be treated as a German then and so he was interned. Yes, that was, was his decision. And he, yes, he found internment interesting, you met lots of people, and, you know, lived in an in a different manner. He always wrote very detailed letters to my mother, which she smuggled out. They each smoked Capstan 333 cigarettes in their identical packets. And during their visits, these packets would be sort of unobtrusively exchanged. And letters, which of course, you were only allowed to write short censored letters from internment camps. But my father wrote very long letters. And so he created a record really, of what, what was going on there, which was perfectly proper, and as far as the Australians went was more a matter of how different people experience this and their problems, really. And my mother was very good, because she then, my father was then taken to Long Bay, which was in Sydney, of course, and so she insisted on taking us to see him very soon afterwards. And so and there, the guard was very nice. I think my parents had to sort of talk through a window with some separation between them but I was then allowed to go into the prisoners room and give him a hug and that sort of thing. And we did when, when my father was moved from camp to camp quite a lot in the early time, Long Bay was sort of the collecting station and yes, we did see him quite a bit until he was sent to Tatura.

LAURA THOMAS: What do you recall of, I guess the emotions that you were feeling when you were visiting him or what you remember of that time?

SILKE HESSE: Yes, I knew that he was. I missed him. But I knew that he was all right. And he also started writing stories for us, which made connections. Yes, we visited him. I visited him too in the camp where he was at was Orange. It was on an oval, I think, on the grandstand. I remember, I had my fifth birthday, I think, or something there, one of my birthdays. And because we knew that he was, I mean, not with us, but he was somewhere and and he could be contacted, I wasn't, I mean, I was a bit sad. But it wasn't, wasn't a traumatic experience. And I think also because both parents were very, very self controlled, and always gave us the impression that they were in charge and that they were sort of were managing their life.

LAURA THOMAS: And so shortly after your father was interned, you and your family, the rest of your family were then interned. Tell me about that experience. Firstly, about the people coming to your door and taking you away from your home.

SILKE HESSE: Yes, we weren't interned straight away. We had about another two years, I think, where my mother and my aunt, we moved to the Blue Mountains. And there were more and more people who didn't, didn't like us, you know, who said their children couldn't play with us or whatever it was. And I think at some stage, it also the lease on the house that we were in ran out. And I think my mother then decided that it would be, my aunt, who'd been helping her, was interned because she was German. My mother was also dual nationality. And so I think she more or less arranged for us to be interned. And I don't really remember, I mean, I remember driving down to Liverpool camp, with two navy blue policemen in the front seats, and the four of us in the back. And then I remember being at Liverpool, and again, one of those nice soldiers in khaki, called us to the gate and said we were allowed to go out and play outside the gate, he had let us go outside the gate and play, which wasn't any more attractive. But he obviously wanted to make the point that children weren't weren't enemies as far as he was concerned, which, which is lovely. So it was sort of these two groups of people in the Australian community, really the ones that were particularly nice and the ones that felt they had to fight us in some way.

LAURA THOMAS: Why do you think your mother decided that you would be interned? What was behind that decision for her?

SILKE HESSE: Oh, well, I think I think she just, she had no help anymore. And both my father and my aunt were interned, and the house lease, she couldn't get a house, she couldn't get anywhere because everybody was coming up to the Blue Mountains away from the sea, which was considered more dangerous. And by then, of course, the Tatura camps had been built. And there were quite a lot of her German friends were there too. And it seemed best for her to have us all together and to be with other Germans. My mother was sort of quite a loyal German. She'd been brought up as, as such and she found it difficult. My father was really much more between the nationalities than she was. Yes. So that was the main reason I think.

LAURA THOMAS: So tell me a little bit about to Tatura. What was it like?

SILKE HESSE: Yes, when we first arrived, it was still a fairly primitive camp. And we were shown the rooms. It was in winter that we arrived and the walls only went up about three quarters of the way. And then there was a big gap with wire across it and then corrugated iron roof. And so the wind just swept through. It was good ventilation but not good in the wintertime. Yes. And, of course the furniture was very primitive, the rooms were very small, they managed sort of two beds fitted in. We then had two rooms for my aunt and three children and my parents, which was quite crowded. Eventually, authorities decided to line the huts, which was very, very good, but the lining had bedbugs in it. And so from then on, there was this fight against the bedbugs and all the furniture had to be moved, or whatever. It wasn't much furniture but everything, all the possessions had to be moved out of those little rooms and into the dust in front of them. And then they'd be sprayed with something and the bedbugs didn't mind at all. They just stayed where they were. And so things like that. I mean, it was very, very tight. And we were quite lucky because our neighbours were Arabs and Italians, mainly Italians, actually. And they spoke quite loudly. I mean, you could hear everything from the neighbours of course, but we couldn't understand it. You know, it was a different language.

LAURA THOMAS: You could kind of drown it out a little bit?

SILKE HESSE: And nobody had much in the way of clothes but we each had, everyone had five grey military blankets. And that was a bit more than than one needed and so the blankets were cut up and made into overalls and all children in the camp were in grey blanket overalls, often with beautifully embroidered bibs.

LAURA THOMAS: Was illness quite rife in the camp?

SILKE HESSE: With us, yes, we just got one illness after the other when we first went into the camps, sort of chicken pox and gastro and then whooping cough and, and that sort of thing. Yes. That certainly, I then became quite frail, I suppose. And I actually had a fortnight in the hospital just to be checked out. When I was older, then still six I think. The food initially was unsuitable there was heaps and heaps of it, particularly bread. And I remember at first sort of, we lived off bread with melon and lemon jam, melon and lemon jam was the universal jam, which is really quite nice. And the cooking was initially in our compound was done by the Arabs and Italians and wasn't really what we were used to. But later a German sort of every every second week and, and a German cook cooked very well. And then there was also people were allowed to then grow vegetables just outside the camp. So there were gardeners who were allowed outside and grew vegetables so that we had much more vegetables and so the food was better that food was always very plentiful. But it wasn't always you know, suitable for children.

SILKE HESSE: And we also had, I mean we were in that citrus growing area, and the German officers who had a camp in the same area, there were about seven camps I think around Tatura, they would send boxes by boxes of fruit for us because they were paid their normal salary which is apparently according to the rules of war, the officers get their salary and so they would spend money on buying boxes of fruit for us. And the German Red Cross sent us rosehip lozenges, which had a lot of vitamin C in them, apparently. We were well looked after from that point of view

LAURA THOMAS: That's great

SILKE HESSE: For men, there were three roll calls a day, for us, as children, there was only one roll call a day to make sure we were still there. There was, of course, barbed wire all around us. And somebody, a khaki soldier in a tower with the gun, which we assumed sort of somehow could could also protect us from enemies,

LAURA THOMAS: Rather than the other way around.

SILKE HESSE: Yes, it was sort of the soldiers were sort of perfectly decent. And in internment camps, the inmates run the daily life. And so, you know, the cooking and the cleaning, and the, and that sort of thing was was done by the inmates. The camp was mainly by that time, when we came was populated by Templars, who were a German group that had gone to the Holy Land and migrated to the Holy Land in I think about 1860s, or something, for religious reasons, and they, their Christianity was really about being a perfect community and loving to each other. So they were very, very good to have there, and they also had experience of internment because they'd already been interned in World War One. So they knew how to do these things. They were then when the war came to Palestine, they were moved out to Australia, and the camp had really been built for them. And so this was a family camp, they also had experience of running schools. So they immediately had schools running for their children, and they knew lots of German songs, which we always sung at school.

LAURA THOMAS: Right, so you didn't miss out on any kind of schooling or education?

SILKE HESSE: No, I was very young. And I was also sort of accelerated. So I was in a class for in which I was really much too young. But I learned to read German fluently, and speak it very fluently. And that stood me in good stead, really.

LAURA THOMAS: And did it feel like for your mother, and from your father's perspective, as well, that it would have been safer to be in this community, then continue to live, I guess, on the outside?

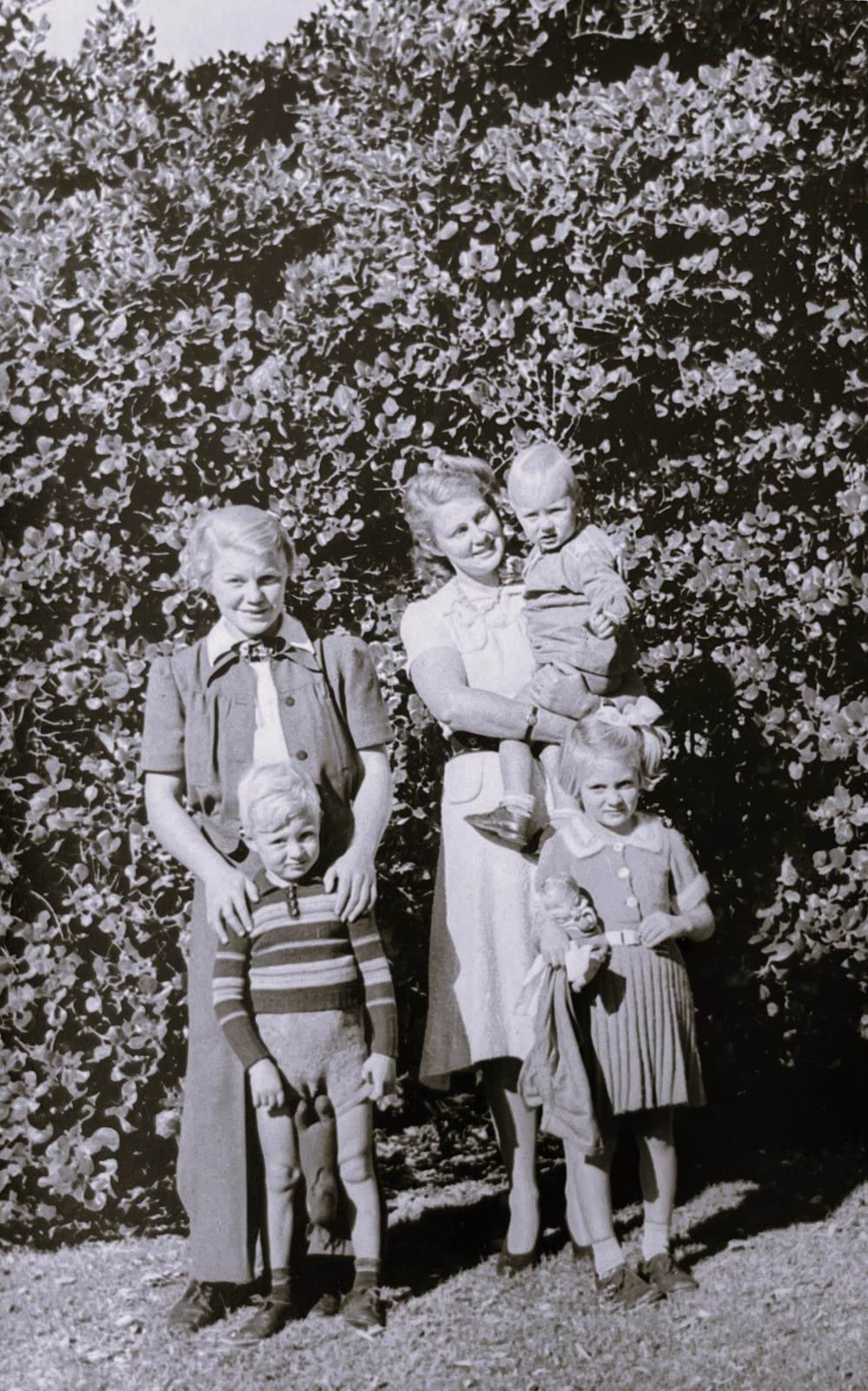

SILKE HESSE: I don't think safety was so much a problem. It was being together. And I think that was very important for us that we had, I remember sort of thinking, "Oh, you know, here, none of our parents could escape or get lost". We were very, very crowded in our two little rooms. And another little brother was born at some stage too. So there were four of us. But I remember it as very happy and because our parents had lots of time, they didn't have to go to work. I mean, people had to do the chores, of course, but then they spent a lot of time writing stories or puppet plays for us and for the other children. And so it was, it was really very good parenting that was taking place. I remember the camp, I didn't feel integrated, but I did, I was very, very interested in everything. And I observed a lot.

LAURA THOMAS: Silka, can you tell me a little bit about these puppets because some of them are on display here at the Shrine.

SILKE HESSE: The puppets were, of course, people didn't have much material. The puppets my parents decided, the first three were made from my birthday that was a prince. a princess and a witch. And, and there was a fairy but the fairy was really sort of mainly clothes I think that, somecardboard or something like that. And it was a fairly fairly simple story. My mother wrote two other more complicated puppet plays, which were then performed. The heads of the puppets, of course, there wasn't really any, any wood that you could use. So they were apple boxes, fruit boxes, where the boards were glued together. And then a Mr. Cooney, he carved them really beautifully. And my mother and aunt made the clothes for them. And they they still exist. Yes. So the next birthday they were an one old men and old woman, and a devil and death, I think, and various others, not all of them had a role in my mother's puppet plays. But yes, they are quite fun. My father also sort of put on plays sort of classical plays for the camp with my aunt usually playing a title role. People managed to enjoy themselves. There was quite a quite a bit of culture going on.

LAURA THOMAS: Yes, and it sounds like despite the circumstances that your parents endeavoured to do everything they could to give you everything that you needed to grow and have a fulfilled childhood, am I correct?

SILKE HESSE: Yes, my father wrote us these stories, because he was worried that we were sort of missing out on nature and that sort of thing. And there were three children, that more or less matched us that lived up in Norway or somewhere in in a very cold, lonely part of the world of pine forests, and, and so on, and had all these adventures there. And, yes, and these stories, of course, were also then read to the other children and, and as we grew up, the children also in the stories grew up.

LAURA THOMAS: Wow, you must have all had incredible imaginations to, you know, to be creating these worlds.

SILKE HESSE: Yes, I think imagination, there's no shortage of it.

LAURA THOMAS: Now, did you ever question why you were there as a child? Did you ever think or harbour any resentment for your experiences? Or was it kind of just normal? This is what life is?

SILKE HESSE: Well, this, this seemed, I mean, I accepted that my parents knew what they were doing. And I accepted that really, without a question, there seemed to be no uncertainty there. And we were looked after and what you know, if we didn't, didn't have a sort of a normal house, then there were other compensations for it. I think my, my problems with the whole war and German business came later. First of all, sort of by the time there was very little communication with Germany during the war, but about a year after the war, then news came that my mother's family had almost been wiped out. I mean, all the brothers and three of her brothers had fallen and so on. So there was there was that, the world was obviously not a safe place at all.

SILKE HESSE: We then also sort of re encountered since we still lived in the same area, the people who had withdrawn their children from the kindergarten because of our German-ness. And I was sent to a private school, a very, very good, nice, nice school. But I was asked not to speak about my experiences. And I felt that if I made friends with people, I think I would be asked about it because I had an accent by that time and and I'd also I was sort of fairly naive to start off with. And so I ended up staying apart from everyone. I always had one friend but I was very excluded from the class, I think and it was partly me, and partly the class, I think that was also uneasy about it. Anyway, I eventually sort of did all right, I became a prefect and sort of was was accepted in that way. But I think the, this feeling that I didn't belong and and that people considered me an enemy, that lingered. And that's really the only damage from the war that I feel I suffered. My brothers had much more trouble when they went back to school, they really had to fight and they had sort of the I think the rest of the class was given victory peace medals, and they were told, you know, because they were 'Huns', they weren't entitled to have one and this sort of thing. So there was much more overt nastiness, and they were much more, they were embarrassed abouttheir German-ness. And so they, they tried to hide it. My mother was insistent that we keep up both languages, which was very embarrassing when you had friends in the house, and somebody was speaking the wrong language. And, yes, so I think, for my brothers, they then made every effort to be as Australian as possible and to deny their German background, which didn't quite work. Whereas I did the opposite. And I kept on reading, my parents had a big library of German books, and I read an awful lot as a child, but I ended up being very isolated.

LAURA THOMAS: Because how old were you when you left the internment camp in Tatura?

SILKE HESSE: I think eight. Just eight.

LAURA THOMAS: So it was really your young formative years that you were separated, and I can see how then that that could impact on later life.

SILKE HESSE: Yes, I think they are very, very important years. And because they were also, I was sort of accelerated. I don't know why that was done. But I ended up being in the fourth class. So I was, I didn't quite fit into the normal rhythms of, of childhood anymore, I think.

LAURA THOMAS: Why were you allowed to leave the internment camp with your family? What was that process?

SILKE HESSE: Well, at the time we left, which was in '43, I think, I think it was pretty clear that Germany was not going to win the war. And we weren't that dangerous. And we were also a big family and a bit expensive, I think. And my father had said that he would very much like to grow food for the Australian people. And couldn't he do that rather than sit around in the camp? And so he ended up, his father's firm was quite wealthy, really. And that money was not lost in the war. And so we could buy an orchard near Orange, two kilometres from Orange. And we had just about every European fruit that you could think of in the orchard. And yes, and went, I mean, that was still, those were still the war years. And because my parents were worried about hostility and that sort of thing, they sent us to a Catholic school. We weren't Catholics, and they didn't have any other non Catholics there, but they took us and they were very lovely to us. So we didn't move back to Sydney again, till after the end of the war.

LAURA THOMAS: And that's where you mentioned that you faced a bit more discrimination.

SILKE HESSE: Yes, so in Orange, really, we hadn't faced, I think the nuns were sort of very kind hearted and Irish. Don't think the Irish minded not being loyal to the English.

LAURA THOMAS: Yes, and reflecting on it now, how do you think that your experiences growing up through war and being in an internment camp influenced you later in life?

SILKE HESSE: Strangely enough, I think as far as I'm concerned, it really gave a lot of richness. There were all sorts of experiences, and I was never really sort of threatened. I learned a lot. I mean, there was, of course, also sadness and that sort of thing. I knew what war was about. I think I didn't resent the experiences ever. I was I was grateful for having had them, which I suppose is a bit peculiar.

LAURA THOMAS: Now, do you have any final reflections or messages that you'd like to share? Based on your experiences?

SILKE HESSE: I think that, from my own experience, this categorising people, according to their supposed nationality, which is a bit haphazard, is not a good idea and the sort of the openness that Australia then opened its doors to all these people that were homeless in Europe. I think that was, I was very, I was proud that Australia did that.

LAURA THOMAS: Some very valuable reflections. And thank you so much Silka, for sharing your story with us today.

SILKE HESSE: Yes. Oh, you're welcome.

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks for listening to this episode of the Toys, Tales and Tenacity podcast series, and a special thanks to Silke Hesse for sharing her memories with us.

Here at the Shrine, we often hear stories from decades gone by and with time, some details can become blurred. Here are a few corrections from Silke and I's conversation:

Silke's father Ekke left Australia for Germany in 1911 when he was 12. He arrived in New Guinea at Christmas 1927 and returned to Australia in April 1930. The New Guinea expedition in which Silke's father participated ended in February 1930. It was financed by a German consortium but one of the three prospectors, the one who died, was a Russian.

Silke was 3 years old when her father was interned on 12th July 1940 and she celebrated her 4th birthday on the grandstand of the improvised internment camp at Orange in August 1940.

Silke's mother Irmhild and her children were interned on 12th May 1942, 3 months before Silke's 6th birthday.

Silke’s family were released onto their orchard, 2 miles out of Orange, in September 1944 and returned to their house in Sydney in early 1946.

This series accompanies the Toys, Tales and Tenacity exhibition, which is on display at the Shrine of Remembrance until August 2024.

The exhibition delves into the experiences of children during war, shedding light on their unique perspectives and the profound impact war has had on their upbringing. To learn more, head to the Shrine website – shrine.org.au

This was one of three episodes in a series of conversations about how conflict has impacted the childhoods of three different people. To hear the rest of the series, search Shrine of Remembrance wherever you get your podcasts.

Updated