Kat Rae is an artist and veteran of the Australian Army who has transformed her experiences with Defence into striking art.

In this episode of Shrine Stories, we learn about the inspiration, process and message behind Kat's series of reduction linocut prints that depict the mountains of Afghanistan.

To follow Kat's work, head to katrae.net(opens in a new window)

Content Warning

This episode discusses themes of mental health and suicide that may cause distress. If you need support, call Lifeline on 13 11 14. For a full list of support services, head to shrine.org.au/wellbeing-resources.(opens in a new window)

Music

Across the Line, Lone Canyon

Transcript

LAURA THOMAS: Here at the Shrine, we have plenty of art on display from all theatres of war, and in this month’s episode of Shrine Stories, we’re going to look at a more modern example with a fascinating story from conception to completion. The piece is part of a larger series depicting the mountains of Afghanistan, and is created by emerging Melbourne-based artist Kat Rae…

Beyond her art, Kat is also a veteran of the Australian Army and joins me now to unpack these pieces. Hi Kat, welcome

KAT RAE: Hi, Laura. Great to be here.

LAURA THOMAS: Now, I thought you could start by talking a little bit about your service and your service history.

KAT RAE: Okay, I joined the Australian Army in the year 2000. I was joining an army that had had a long peace beforehand. So I was motivated by the blue beret work that we'd done in Somalia and Rwanda and most certainly East Timor. And I was really interested in the military humanitarian side of our defence force. It sounds quite naive now. But at the time, there was recruitment drives and posters with medics holding children getting survivors from disasters. And I wanted to be a part of that. So I signed up. And my second year into Australian Defence Force Academy, September 11 happened. And that really changed the way that my 20 years of serving in the Army went because it was very Middle East orientated.

LAURA THOMAS: So 20 years was your full career?

KAT RAE: That's right. Yes. So I did Australian Defence Force Academy and then Duntroon. And then I posted from Hobart, Darwin, and lots of places in between Canberra, Melbourne, Sydney, and I deployed three times. I was in Kuwait as a platoon commander in 2007. And then I was second in charge of a workshop in Afghanistan in 2009. And then later, I was an Afghan security force liaison embedded with American forces in Kandahar, Afghanistan, and that was in around 2012.

LAURA THOMAS: When you signed up, did you think that you would have those experiences reflecting back on it now?

KAT RAE: Oh, I think I probably thought I'd sign on for like, 10 years or nine years at a minimum. And then one year to get long service. I thought it would be a great start in your life to sort of garner lots of interesting experiences. And I've always wanted to be an artist. So I thought, look at will give me these things to make art about and I'll travel the world. and I'll make friends. And I guess it kind of did do that. Like, yeah, I was kind of amazed at how it really delivered in those areas. And I enjoyed, I mean, obviously, I enjoyed it so much I stayed for another 10 years again.

LAURA THOMAS: So you mentioned that you always had an interest in art. But how did you go from this varied 20 year career in this environment to then becoming an artist and doing what you do today?

KAT RAE: Well, when I joined ADFA, I'd also concurrently got into some more creative courses down in Melbourne, I decided to give ADFA a go. And then throughout my career, I'd always join the local gallery, or the art community wherever I was posted and do little courses along the way. And so I was always kind of keeping a practice going along the way. And then I guess, I just felt like after a while that I couldn't spend another 20 years in the Army, I really wanted to pursue something that was artistic. My husband who was also serving died in 2017. And we had a two-year-old together, we'd been together for 13 years. So suddenly, I was solo parenting and serving full time as well. And I found the difficulty of that balance extremely hard. To parent like you don't work and to work like you don't parent was really difficult. And as supportive as Defence Force was sort of, especially initially, I think as time was going on, I think there was sort of a feeling that I got that I just had to kind of keep performing to that same level and it was just really hard. I kind of felt burned out and I remember speaking to a friend who had known me from my first week at ADFA, and we'd stayed good friends. And he said, 'Why didn't go back to the arts, you've always loved that'. And I just thought, 'Well, maybe I'll explore it'. And I had to work out of Melbourne for a little while. And in my lunch breaks, and outside of work, I visited all the art schools in Melbourne. I'm from Melbourne originally, my family were down here. So it was already really hard for me to serve in Canberra away from all my support networks. And I just could see myself there. And I thought, 'Well, I've spent, you know, I've done, you know, an undergrad and two masters studying in the Army, what would it be like to study something I was really into, and really passionate about?'. You know, the fact that I was, you know, I felt kind of capable and good at my job in the army. It was probably never the most perfect fit. So what would it be like to be in a career where it was a perfect fit, and it was something that I always really wanted to do. So I decided to leave the Defence Force and pursue the arts. And, yeah, I got some time to walk the Camino in Spain, which is a 700 kilometre trek. And in that time, I was able to really thank the army for, you know, the ease that I had in carrying a pack every day. The ease that I had in walking all day, every day for five weeks and meeting people from all around the world and finding commonalities there. And at the same time, I was immersed by the art and the architecture and the nature. And it was kind of a fantastic way to sort of say goodbye to a really, mostly positive 20 years of my life, and hello to a new career of the arts.

LAURA THOMAS: So did that help make the transition from military life back to civilian life, as it's called, a little bit easier? Because we often hear that transition can be quite a difficult one.

Yeah, I mean, I do think the transition is a difficult one, I joined when I was 18. And my entire adult life was in the service, in the institution. So I think, doing a sort of rite of passage, like the Camino, it was helpful. I think another part that was helpful was joining another institution, and that being art school, because of that, I had a routine, I'd been given a new cohort of people to become friends with and connections into the industry. And I had the discipline of making projects and actually producing so I think, having, you know, proper study, and, and luckily, you know, full time study was an excellent transition. There's an organisation called Australian National Veterans Art Museum, as well. And they really helped me translate my experience in the Army, to the arts. And they helped me put a portfolio together and helped me prepare for interviews, and really helped kickstart a new career as well. So I'm very grateful to ANVAM as well.

LAURA THOMAS: They're a great organisation. And if anyone is listening, and they haven't been down to the galleries, I would strongly recommend it. But we've spoken about kind of the way that they helped you create art, and we're going to talk now about some art that you've got up in the galleries of the Shrine of Remembrance, it's part of a larger series on mountains. I'd like to know Kat how these pieces, we've got a couple of them in the Shrine collection, how they came to be. Talk me through that process.

Yeah, these artworks were exploring the idea of mountains and in particular, the Afghan mountains that I'd seen, particularly when I was deployed to Tarin Kowt, because they're just draw droppingly beautiful, natural features where we were deployed, and also coming to terms with the death of my husband and the fall of Kabul, to the Taliban. And it was coming up to the four year anniversary of my husband's death. I never sleep well that night, just remembering. And I checked the news on my phone, and I saw that Kabul had fallen to the Taliban, and there was awful scenes out of the International Airport. And I just, it was like a culmination of being locked down in Melbourne for what felt like years, and adjusting to being a full time serving member to being a full time art student. And yeah, just the sadness of my time. I'd spent at least a year in Afghanistan all up. And yeah, the weight of the grief. And it felt a bit like the futility of the death of so many people and the hopes and dreams of so many Afghans.

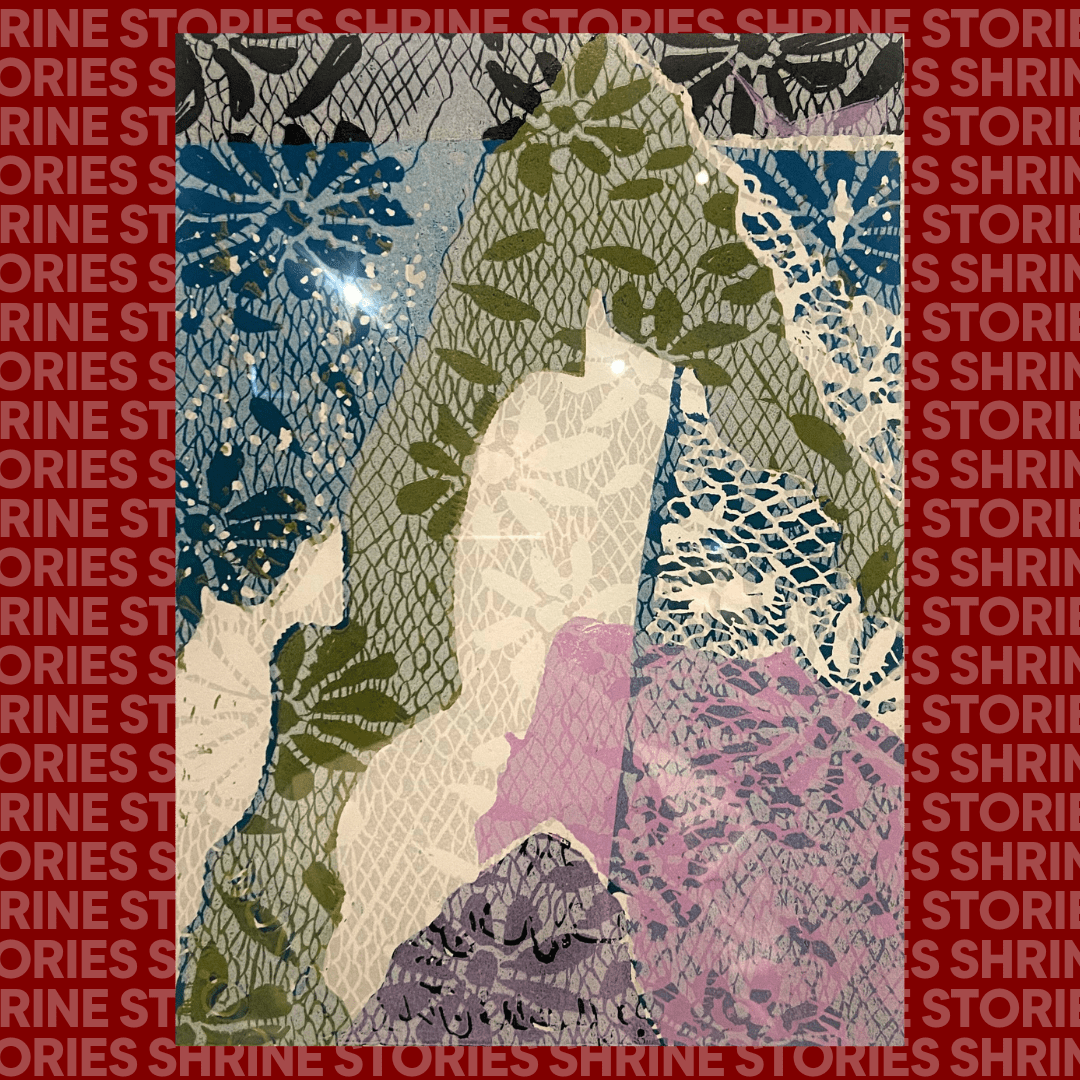

KAT RAE: So when I got up the next day, I worked on a collage. And I went through all my military books and my book shelf and I have lots from my time from studying at War College and I had lots of papers which I kind of ripped out and re assembled as mountains of Afghanistan. And I guess for me, the mountains had always represented the of human and natural history and the longevity of war, especially in that region. And I used texts which spoke to that. So, you know, there was the History of the Peloponnesian War and Clausewitz's 'On War'. There was Lawrence of Arabia's work. I had elements from Vietnam, I had a publication called 'Khaki and Green', which was made in 1943, which was all about Australians experience of World War Two. And I even had things from Goya's 'Disasters of War', which he really highlights the suffering of women and children in war. I had a CIA pamphlet from the Soviet War in Afghanistan, and also had Andrew Quilty's article from The Monthly where he spoke about the war crimes in Afghanistan. So I tried to cover a full spectrum of war as well as you ever possibly could. And tried to build up these mountains in this collage that spoke to that. The shape of that mountains also echoed the burkas that women were wearing in Afghanistan, and, and the costs on women and children throughout that war in particular. And then I was able to crop those collages,the three collages which are actually hanging at ANVAM. And if anyone wanted to see them, they're opposite the Shrine at ANVAM, but I cropped them down and took a small segment of them, and then turned it into a reduction linocut print.

LAURA THOMAS: What is a reduction linocut print? For people like me, who maybe aren't in the art world? Can you explain that?

KAT RAE: Yeah, so linocut is like a woodcut, except it's made on you know, a plastic or plastic kind of piece of material, where you have cutting tools, and you carve out your image onto that, and then you print it. And as you print it, the reverse is done. So I've find, when you explain printing to people, their eyes glaze over immediately, there's a certain magic in actually doing it in real life. But when you actually are talking about it, it's something just doesn't translate. Picasso used to call the reduction linocut the suicide print. Because as you carve, you keep printing different colours over layers, and layers and layers. And you keep carving until there's nothing left. And the lino that you're cutting out of called the matrix, which also translates to mother.

KAT RAE: So I kind of, there was lots of echoes in my own life and the nature of suicide in the veteran community as coinciding with calls for a Royal Commission into veteran suicide, which we are now having. So I felt like it was a medium, which firstly, built up layers and layers of colour and growth, but at the same time, reduced the body till it was gone. There's also something kind of iterative about print as well, because you do many, many layers. And there's something about trauma, and post traumatic stress, which has flashbacks and moments of that. You apply the print through a press, it's applying lots of pressure, which again, anyone who's experienced PTSD, or knows someone who has that would also see the echoes of that in the work as well. And also, it's really slow work. Like it took me months to make this really, I mean, I made the collages in a few days, it was kind of a frenzy of work, but then actually to painstakingly carve and really intricate flowers and lace work and design and to build this up. And I had Arabic lettering in there as well. It took a long time to make it work. And I think anyone who's recovered from their experiences of war, would kind of understand the importance of slowness and slowing down and the power of slow art as well.

LAURA THOMAS: Right. And something really interesting about these artworks is their titles, which are based off an Afghan proverb. The one we've got hanging up at the moment is titled, 'Even on a mountain, there is still a road'. Why did you choose this proverb in particular, for these artworks?

KAT RAE: Yeah, so that title is, is named after an Afghan proverb. When I was in Afghanistan, I met so many Afghans, and I was just really blown away by their resilience, tenacity, their hopefulness in their country, their pride in their country. And I really wanted to reflect an Afghan centric view of that war in a way that I could, that I felt like they had something really powerful to teach us about post traumatic growth, and coming through a difficult suffering time. And yeah, I just felt like that was something that we could all kind of try and remember that even in the most difficult times there is a path to the top.

LAURA THOMAS: And something else that strikes me about these works is the colours that you've put in them. Without wanting to stereotype, they are quite feminine colours. There's lots of pinks and purples. Was that a conscious choice by you? You've spoken about kind of that feminist angle on it? Was that something that you had in mind when you were choosing the colours for the pieces?

KAT RAE: Yeah, absolutely. The Afghan aesthetic has a certain, I hate to use the term feminised, but when I went into the Special Forces Afghan headquarters, the interiors painted a pastel pink and had painted roses all through it. And the first thing that Afghans did when they had a new barracks was they would plant a rose garden. And, you know, this really struck me as something very, very different to our own special forces headquarters where you go into and it was sort of like the feminine was kind of exercised out. It was kind of dark and hard and opaque. So I was really interested in how Afghan culture kind of jazzed things up and lent into the beauty of things, you know, their trucks were beautiful, dazzling jingle trucks, and even you know, the the rubbish trucks were like this, there was so much pride. When there was enemy weapons captured, it would often be decorated or you know, their equipment was decorated as well with tassels and colour. And I kind of really was taken by the way that in the West, these kind of ideas are kind of feminised, there's kind of a feminised way of seeing things in a way of decorating whereas they really lent into that, and I thought that was quite beautiful.

KAT RAE: when I made the artwork, I really wanted to have the beauty of the colours reflected in there, I mean, the colours of the mountains as well were in the changing light, purple, and green and tan and white. And I just thought they were just beautiful colours that I really wanted to reflect. And they weren't the kind of colours that people thought of when they thought of war. When I showed the work to the Shrine of Remembrance, someone in the art collection said, 'Oh, they're the suffragette colours of purple, white and green'. And I had not noticed that about my work. But I had spent a lot of time at the National Gallery of Victoria, looking at the suffragette artwork and being taken by their colours and taken by their aesthetic. And it was a really interesting observation that yeah, they sort of had, by osmosis filtered into my work as well.

LAURA THOMAS: And I think you have a really interesting perspective being a woman in the Army. And you've mentioned that you- it's reflective of the wars effects on women. How did you take those experiences and what you witnessed around women and children in Afghanistan and translate it into your work?

KAT RAE: When I met Afghans who had studied in Afghanistan doing law degrees in Kabul, they said half of their class was women, and they wore miniskirts. And you know, when you visited Afghanistan now, it's it's the opposite, you know, and I just, it made me really reflect on how handmaidens tale-esque we can lose our rights. And, you know, the devastating effect that war has particularly on the most vulnerable, the civilian populations. And by default, mostly women and children. The gendered lens seemed to be so... you couldn't help but see that the difference between that, you know, since coming back, I was a, I became a war widow. And I'm a mother. And I reflect on the experiences of the war widows.

KAT RAE: When my husband died, I was at Staff College, and there was a Major who was studying with me, he was from Pakistan. And he just assumed that after I was widowed, I would drop out of the course and I wouldn't have a career, and I would pretty much be begging for survival. And he was just blown away that I kind of kept back and I kept my career going. Because it's just totally different over there. There's no support for them. So not only are they suffering, you know, the worst out of the war in so many ways. The iterations of after the war was a stark contrast to me. And that feels really unfair to me as someone who has a different experience just through virtue of the country that I was born in. That's been of interest to me. When I go to war memorials, there's a very, there's a lens that esteems male suffering, male sacrifice, and it forgets anything of the other. It forgets the civilian populations or the places where we fought in. It forgets our own country in the war, the colonising wars that occurred here, and it forgets the iterations of trauma that occurs and I feel like unless we remember the true cost of war in all of its iterations and painful ways, it's too much, it's too easy for us to kind of go back again, and keep fighting, or stay silent on the wars that we should be speaking out about even potentially now.

LAURA THOMAS: With that said, and I know, this is a big question, what do you hope people take away from this series and these artworks in particular?

KAT RAE: I hope that they can think about war in a more multi dimensional way. That they can try and see the layers of my artwork, and think about the layers of cost and, and suffering of war. But I also hope that they can see the message of the mountains, and that there's a path to even the top of every mountain. And see a hopefulness as well, you know, post traumatic growth is a thing, and it's a lifelong benefit of struggling through suffering, and, and finding a way forward and finding a purpose and making connections with people and seeing the world in a different way. And it's a gift that we all have, if we are lucky enough to have post traumatic growth. So for me, I hope that that shines through the work as well.

LAURA THOMAS: Beyond this series, do you think that your service has influenced a lot of your other pieces of art?

KAT RAE: Absolutely, you know, I think I hoped that when I left the Defence Force and went to become an artist, that I would make art that was light and different, and about things that weren't defence related. And maybe I'll get to that at some point. But I feel like, there has been a deep vein of interesting things to make art about through my experience of war. There's not many contemporary artists in Australia that have also had such contemporary experience in serving, and certainly in the places that I have, as well. And I joined a community of veteran artists, which has been warm and embracing and very encouraging. And that's been fantastic. And I think what they say is, you know, all different. Everyone has different takes. And I feel like they've got important things to say about their experience. And through art, you can explain yourself.

KAT RAE: For me, I've always been interested in protest art, and bringing art to the people. And, you know, when I served, I wasn't able to really speak my mind, because you can't really. You need to be bipartisan, the forces need to be bipartisan. And not only that, but serving members really can't be vocal about how they feel about certain topics. So for me, it's kind of been an emboldening and enlightened experience to be able to actually say things about my experience in a way that I feel is just so important. Because if you don't, we are going to keep getting ourselves into wars that are deeply unhelpful. We will not change the laws, which needs to be changed. You know, I feel like as climate change continues, war is going to be more about resources. And again, when I make art about the mountains, I'm talking about, you know, the power of nature and how we need to protect it and how it's been destroyed by so many things; colonisation, the military industrial complex. And I feel like, you know, when, you know, the biosphere is collapsing, we don't have time to waste on wars that aren't a necessity. One artist said that 'Beauty is the Trojan horse for artists to be able to share big ideas'. And so I think even on an aesthetic level, it is something that's appealing, and then maybe as you look through it later, you can see a deeper meaning again,

LAURA THOMAS: Kat, it's been fascinating talking to you about your art, your service and this series in particular, where can people find you and follow your work?

KAT RAE: Oh, thank you. Well, come to the Shrine of Remembrance

LAURA THOMAS: That's the first stop

KAT RAE: And see the work there in the contemporary Afghan gallery also. Also ANVAM holds my work particularly the originating three collages, which I spoke about me making on the fall of Kabul, and you can read more about my work and see more images on my website, which is katrae.net. I'm also my Instagram which is at kat_a_rae.

LAURA THOMAS: Brilliant, thank you so much Kat, it's been great talking with you.

KAT RAE: Thank you.

LAURA THOMAS: Thanks for listening to this episode of the Shrine Stories podcast. Make sure you subscribe to our channel wherever you listen to stay up to date with the latest episodes.

If this episode raised any issues for you, know that help is always available.

Open Arms is a Free and confidential, 24/7 national counselling service for Australian veterans and their families. To contact them, phone: 1800 011 046

You can also contact Lifeline for support on 13 11 14.

Updated