- Conflict:

- Second World War (1939-45)

- Services:

- Navy, Nursing services

Dean Bowen first encountered the story of the doomed 2/3 Australian Hospital Ship Centaur when the vessel’s wreck was found in 2009, off Queensland’s south-east coast.

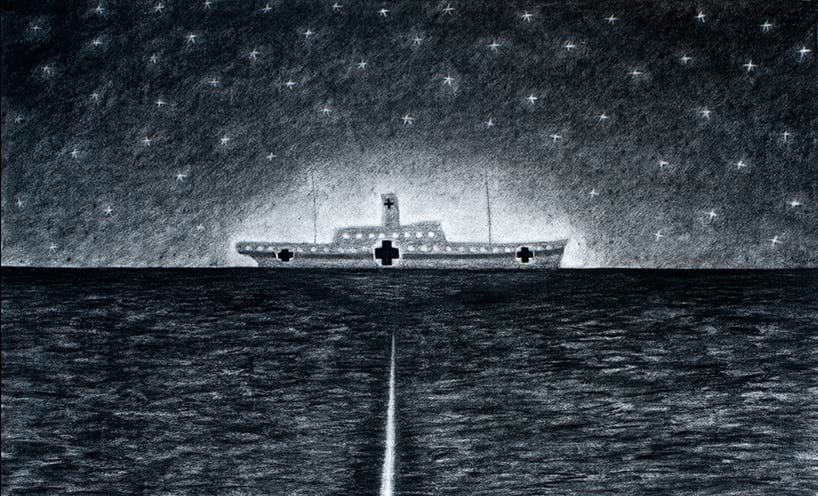

The award-winning artist and sculptor was deeply touched; he responded to the discovery with a series of charcoal drawings. The beautiful, unsettling, works form the backbone of a Shrine special exhibition to be launched in July 2020.

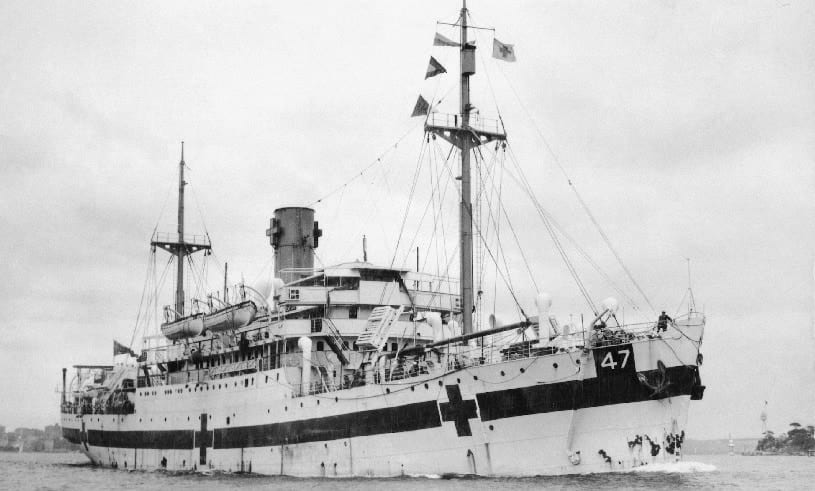

The tragedy of the 2/3 Australian Hospital Ship (AHS) Centaur began at, or soon after, 0400 hours on 14 May 1943. Centaur—situated 80 kilometres east north-east of Brisbane, south of Moreton Island, and heading north—was struck portside by a torpedo, fired without warning by the Japanese submarine I-177.

Penetrating the hull, the torpedo ignited an oil fuel tank and generated a tremendous explosion. Centaur’s bridge superstructure collapsed and its funnel crashed to the deck. Burning oil splattered across the ship and fire soon engulfed the vessel. As water surged into the shattered hull, Centaur rolled to port and plunged, bow-first, into the deep.

Most of those aboard Centaur were asleep below deck when the torpedo struck and had little, or no, chance of survival. Those not killed outright by the explosion and subsequent inferno, were stunned and disorientated. Navigating the maze of narrow corridors and bulkheads running through the heaving and disintegrating ship proved to be a task few could manage. Those who did succeed in reaching deck level (a somewhat abstract concept at this point) jumped into the water—there was no time to lower life boats, though two boats would miraculously break clear. Within three minutes, Centaur, and hundreds of people still enclosed within, had sunk beneath the waves.

The two damaged lifeboats and other flotsam breaking loose from Centaur during its rapid descent, provided makeshift rafts for the still-living individuals adrift in the water. Many were lucky to have survived even to this point. The vortex generated by the sinking ship dragged many castaways to their death.

Those wearing life jackets would eventually be propelled to the surface but their survival depended entirely on dumb luck—i.e., the amount of time they were kept below the surface and whether they were lucky enough to avoid fatal collisions during their rapid ascent. Among the victims who did succeed in reaching rafts were several who died all the same: from shrapnel wounds, burns and shock. Of course, many would never reach a raft. They drowned or died of exposure.

In the immediate aftermath of Centaur’s sinking, terrified survivors were forced to brave the stomach-churning sound of I-177’s engines rumbling across the waves and the sight of the submarine’s ominous silhouette against the horizon. Extinguishing all rescue flares, the castaways may well have saved their own lives but the blackness did little to assuage their fears.

Thirty-five hours passed before the survivors were rescued by the crew of the American destroyer USS Mugford. In the intervening period, the survivors would repeatedly have their hopes raised and dashed, as four ships and as many aircraft passed by without spotting them.

Centaur’s complement immediately prior to the attack was a medical staff of 52 men (including eight doctors), 12 army nurses, and a civilian crew of 75 merchant seaman. Aboard too, 193 members of the 2/12 Field Ambulance en-route to Port Moresby. Of these 332 souls, only 64 would survive.

Centaur was marked with red crosses and floodlit, as stipulated under The Hague Convention. An identifying number—47—had been lodged with the International Red Cross and the Japanese government. The sinking was a war crime. Nothing less. News of the outrage shocked the world.

Centaur remained a household name in Australia for many decades after the war. Memory of the disaster was undoubtedly fading when the wreck was discovered off the south Queensland coast in 2009 by an oceanic survey team led by renowned shipwreck hunter David Mearns. Mearns’s previous triumphs included the discoveries of the German battleship Bismarck in the North Atlantic in 2001, and closer to home, HMAS Sydney and its nemesis HSK Kormoran, off Carnarvon, Western Australia in 2008.

The discovery of Centaur’s wreck and haunting footage taken of it by Mearns’s team, served as a lightning rod for contemporary artist Dean Bowen. It immediately inspired a series of interpretive charcoal drawings which Bowen has continued to create ever since. Quirky, vibrant compositions—depicting people, animals, everyday places and objects—are hallmarks of Bowen’s award-winning, internationally-renowned work. The Centaur series, however, explores much darker territory than is typically Bowen’s wont. His child-like vision amplifies the horror of the events of 14 May 1943. The beautiful, unsettling work underscores the horror of the violation, considered by many experts to be among the greatest war crimes ever committed against Australians.

In July, the Shrine will launch a new exhibition built around Bowen’s Centaur series, examples of which will be utilised in a specially commissioned animation by Japanese audio-visual artist, Ayumi Sasaki. The animation will incorporate a soundscape by musician Guy Burgess and feature excerpts of the epic poem, Hospital ship Centaur by Paul Sherman as well as ABC archival footage of interviews conducted with survivors of the sinking in 1943.

Memorabilia on loan from the Australian War Memorial, The Centaur Fund, AHS Centaur Association and the families of victims of the tragedy will provide a tangible reminder of the event, remote in time, but whose after-effects remain with the families of Centaur victims to

this day. Immersive light projections, unlike any the Shrine has utilised before, promise to provide a heightened emotional experience for visitors.

Exhibition co-curator, historian, Dr Madonna Grehan, a past President of the Australian and New Zealand Society of the History of Medicine, has been heavily involved in the project from the beginning. Among the world’s foremost experts on the sinking of Centaur, Grehan has provided invaluable advice to the Shrine. She is assembling a host of loans from across Australia to demonstrate the myriad ways in which the tragedy, its victims and survivors have been memorialised since 1943.

The most famous victim of the attack on Centaur is undoubtedly Sister Ellen Savage. The strong swimmer was the only nurse of 12 aboard to survive the atrocity. Suffering severe bruising, a fractured nose, burst ear drums, a broken palate and fractured ribs, Savage nonetheless managed to join other survivors on a makeshift raft. Concealing her own injuries, she assisted her comrades, many of whom were severely burned. She raised their morale with group prayers and singing and supervised the rationing of their scanty water and food supplies.

In 1944 Savage became the second Australian woman to be awarded the George Medal for ‘conspicuous service and high courage’. She later became a founding member (1949) and President (1957–58) of the College of Nursing, Australia and was actively involved in establishing Centaur House, Brisbane, an educational centre for her profession. It is therefore unsurprising that her story will be one of the highlights of the exhibition.

Author:

Neil Sharkey has been a curator at the Shrine of Remembrance since January 2007. He developed the Shrine’s Second World War Gallery as well as dozens of temporary exhibitions, including his most recent The Cinderella Service: Australians in Coastal Command 1939–45. Imagining Centaur opens in July 2020.

Updated