- Conflict:

- First World War (1914-18)

John Williams made an important contribution to Australian photography, from the moment he looked through the lens of his camera in the late 1950s. He was known for his documentary street photography that exposed a rawness in the subjects he captured; people caught up in unselfconscious moments, immersed in what they were doing.

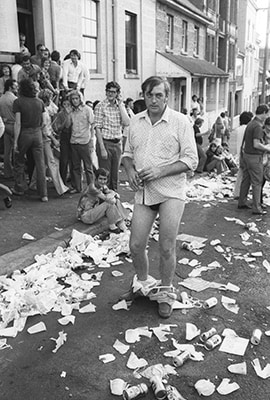

He had the ability to dispassionately confront the viewer in a unique way; his images often unveiling complex or uncomfortable truths about society and culture. His series of images taken in the 1970s in the Rocks, Sydney epitomised this ability to hold a mirror to the world around him. In this series, John captured the ugliness of ‘Aussie larrikinism’—a predominantly masculine culture, out of control, caught up in a spiral of drunkenness on the ubiquitous ‘pub crawl’.

Courtesy of John Williams’ estate

John’s critical ability was most fully realised in his preoccupation with the First World War. Documenting the facets of the history and impact of the First World War was a constant in his photography and writing. It stemmed directly from traces of the war in his own biography, through his veteran father, Frank Williams.

Frank served with the British forces as a Sergeant in the Liverpool Regiment, 55th West Lancashire, Red Rose Division, on the Western Front. After he returned home, he decided to immigrate to Australia; seeking a warmer climate for ongoing health conditions sustained as a result of exposure to mustard gas. He had narrowly escaped death, after being seriously wounded by shrapnel and, like many others, carried physical and psychological scars for the rest of his life.

John was deeply affected by his father’s experience, stating his own existence was a miraculous outcome that would not have been possible had his father’s shrapnel wound been ‘an inch to the left, or penetrated a fraction deeper’. The impact of the war on his father’s life trajectory was in fact, the reason John Williams was born.

The legacy of war is not solely experienced by veterans or civilians caught up on the front lines: it spirals out from events, it cascades through the decades and between generations—for better or worse. Landscapes are changed, economies are affected, relationships are broken or formed, loved ones are lost, psychological scars run deep. John Williams knew this and understood it in a very personal way. He and his mother lived the ups and downs of his father’s nightmares; his incapacity to stay warm even during Australia’s hot summers; his inability to share with them what he had witnessed and experienced. He absorbed the attitudes expressed by his father about the ghastly reality of war and developed a distrust for anything that glorified war.

According to John, neither his father nor uncle Cyril, who had served as a Lieutenant with the Australian forces, marched on Anzac Day. Neither ‘wanted anything to do with commemorating war in any form’. Like many returned servicemen, the memories were too overwhelming and the two only talked between themselves, after a few drinks at Christmas.

This tension, trauma, suppressed emotion, circumspection and cynicism was a constant low hum in the background of John’s life growing up. It fuelled his curiosity and obsession with the First World War and its reverberations through history.

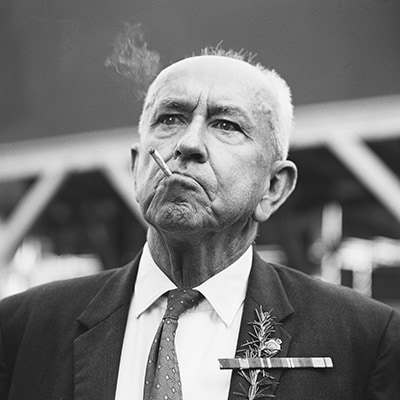

The first time John reflected on the war experience was in his series of Anzac Day images. Beginning in 1964 and ending in 2003, Williams photographed veterans and spectators at Anzac Day parades in Melbourne and Sydney. Whilst his attitudes to the event were complex, his images of veterans provide a window into the emotional lives of these men.

In Anzac Day, Sydney, 1964 we see the close-up portrait of a man, possibly in his 70s, cigarette in mouth, his ribbons and sprig of rosemary visible on his jacket, staring intently into the distance. The object of his gaze is not in view to us. Is it because it is not a physical object that his gaze rests on? Does it rest instead, on memories? Whilst at first glance we might see the face of a staunch veteran, if we really take in the moment, we see the deeply etched emotion in the eyes and mouth of the man in front of us. Perhaps he is reliving all the pain of his war experience.

In a later series of works, taken on a trip to France, John documents the landscapes and memorials where veterans, like the one in Anzac Day, Sydney 1964 and his father Frank, had their nightmares and scars imprinted on them.

In 1991, during a three-month residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, John visited sites on the Western Front including: Australian Cemetery and Memorial at Fromelles, Australian National Memorial at Villers-Bretonneux, Fricourt German Cemetery and Lochnagar Mine. The photographs, which were never printed or exhibited in his lifetime, demonstrate John’s unique manifestation of the way the impacts of war can be felt across time and space, and across cultures.

John felt alienated from the grand and imposing memorials he encountered, yet his camera reveals beautifully distilled, haunting, poignant images that offer the essence these landscapes and structures represent: the sombre reality of war and its capacity to forever make a mark either on our individual or collective psyche or physical world.

Western Front Series

Untitled 1991, unknown memorial, Western Front Series, shows a landscape containing a small group of recently pruned trees with a large cross. The site does not have any hallmarks of an official memorial by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, rather, it appears to be a local marking of a site where lives were lost during the war. John was attuned to the significance of the uneven ground and the appearance of mounds across the landscape as tell-tale signs of mass graves. The cut branches and lonely tree stumps seeming to represent life and death, renewal and regeneration.

Lochnagar Crater

Western Front Series

Untitled, 1991, Lochnagar Crater, Western Front Series, captures the echoes of the war across time. The crater was formed by the detonation of a British mine on 1 July 1916, when the Battle of the Somme began; the landscape forever embossed with the ferocity of the explosion. So too, in Untitled, 1991 bullet holes, Western Front Series, the facades of old buildings are pocked with bullet holes - still there in 1991 for all to see.

Western Front Series

Seventeen years’ after John captured the Western Front series of photographs, he discovered that like the French landscape, his own family was still being altered by echoes of the war.

He was researching poetry believed to have been written by his British grandfather and published in the Liverpool Echo when he and his wife accidently discovered a classified advertisement by a James Williams, seeking information about his father. The details made it clear that the man being sought - James’ father - was John’s father.

Although the advertisement was five years’ old, the phone number was still operable. The life-changing phone call by John revealed that he had seven siblings in Liverpool. The only details James and his siblings knew were that their father, Frank, had returned from the war and sometime later moved to Australia. After he left, they had been forbidden by their mother to ever mention his name again.

Despite the obvious pain of a family torn apart and the secrets that ensued across continents and decades, the revelation, at age 75, John was not an only child, but the younger brother to seven siblings and a Great Great Uncle, was a moving and enriching outcome.

Liverpool, United Kingdom

Reproduced courtesy of John Williams’ estate

The continuing thread of the First World War in John Williams’ life was something that made and remade him as an artist, an historian and as an individual. Whilst the influence of the war on his personal life is not an uncommon story for families or veterans, John’s ability to subtly articulate and distil the layered meanings, experiences and impacts of history, through his photography, were unique.

Author:

Kate Spinks is Curator, Exhibitions and Collections at the Shrine of Remembrance.

Updated